„Imagine two horses looking at an early automobile in the year 1900 and pondering their future.“

Gregory Clark’s, Farewell to Alms

The Meaning Behind Two Horses (2020)

The central question of Two Horses challenges the traditional definitions of art: Is art determined by intent, context, realization, or perception? The artwork shares the responsibility of authorship with the viewer, inviting them to reconsider their own role in defining what constitutes art.

By engaging with the work, the audience becomes entangled in its conceptual framework, blurring the line between observer and participant. Art does not come into existence solely through the artist’s act of creation; it also requires recognition by its audience. Does art exist without an audience? A piece, an image, an installation, a video, a piece of music, or a sculpture does not exist as „art“ in isolation. Rather, today’s art is increasingly shaped by conceptual frameworks, narratives, and ideas — especially in the age of machine-assisted creation.

This raises a further question: Are we entering a new era of conceptual art, where the artwork itself serves as a mere vessel for a larger meaning? When artificial intelligence generates the visuals, the music, or even the text, does authorship shift toward the machine, the programmer, the artist, or the curator who contextualizes the work? If artistic manual skill is no longer the primary defining factor, does the essence of art lie in the conceptual intent rather than the technical execution?

This work draws inspiration from the book Life 3.0 by Max Tegmark, which discusses the obsolescence of human labor in the face of artificial intelligence. Tegmark references economist Gregory Clark’s Book Farewell to Alms, using the fate of horses after the advent of the automobile as an analogy for the potential displacement of human workers.

Clark imagines a conversation between two horses in the early 20th century, debating whether they should fear technological unemployment. One horse argues that previous innovations, such as steam engines and stagecoaches, ultimately created new job opportunities. The other warns that this time might be different. History proved the pessimist correct: as mechanical muscles replaced horses, their population in the U.S. plummeted from 26 million in 1915 to just 3 million by 1960.

Two Horses reflects on this historical shift, drawing a parallel to the present moment. As AI and automation increasingly replace human cognitive labor, will we experience a similar fate? Are we humans, like the horses of the past, standing at the edge of obsolescence, convinced that new opportunities will emerge — only to find that they might never do?

Art has always been shaped by the tools available to its creators, from the brush to the camera, from the synthesizer to the algorithm. Two Horses emerged from a simple yet profound question: Who is the artist when artificial intelligence is involved? Is it the human who provides the input, the machine that generates the output, or the audience that perceives and interprets the work? And will it definitely take away human jobs when it comes to art and creativity?

This project was an experiment in surrendering control — allowing AI to generate visuals, music, and even my own voice. It was unsettling, exhilarating, and deeply personal. The act of training an AI with my voice raised fundamental ethical and emotional questions: What happens when my voice no longer belongs solely to me? Who controls what it says? These concerns are not just theoretical—they are real and immediate for many creatives today.

I see Two Horses as a conversation, not a statement. It invites the viewer to step into the role of the artist, questioning where authorship begins and ends. The piece draws a parallel between the obsolescence of horses in the industrial age and the potential displacement of human labor by AI. But unlike the horses of the past, I strongly believe we still have a choice: to define our role in this transformation, to rethink what creativity means, and to shape the future of art.

Visual and Auditory Analysis

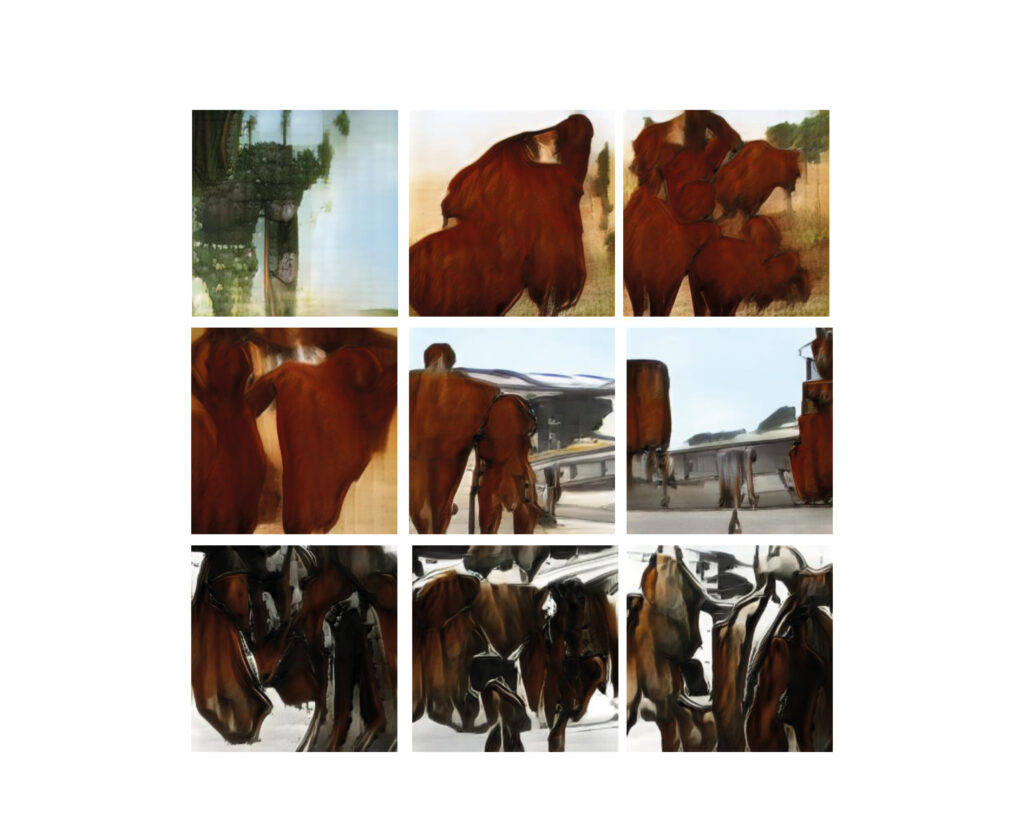

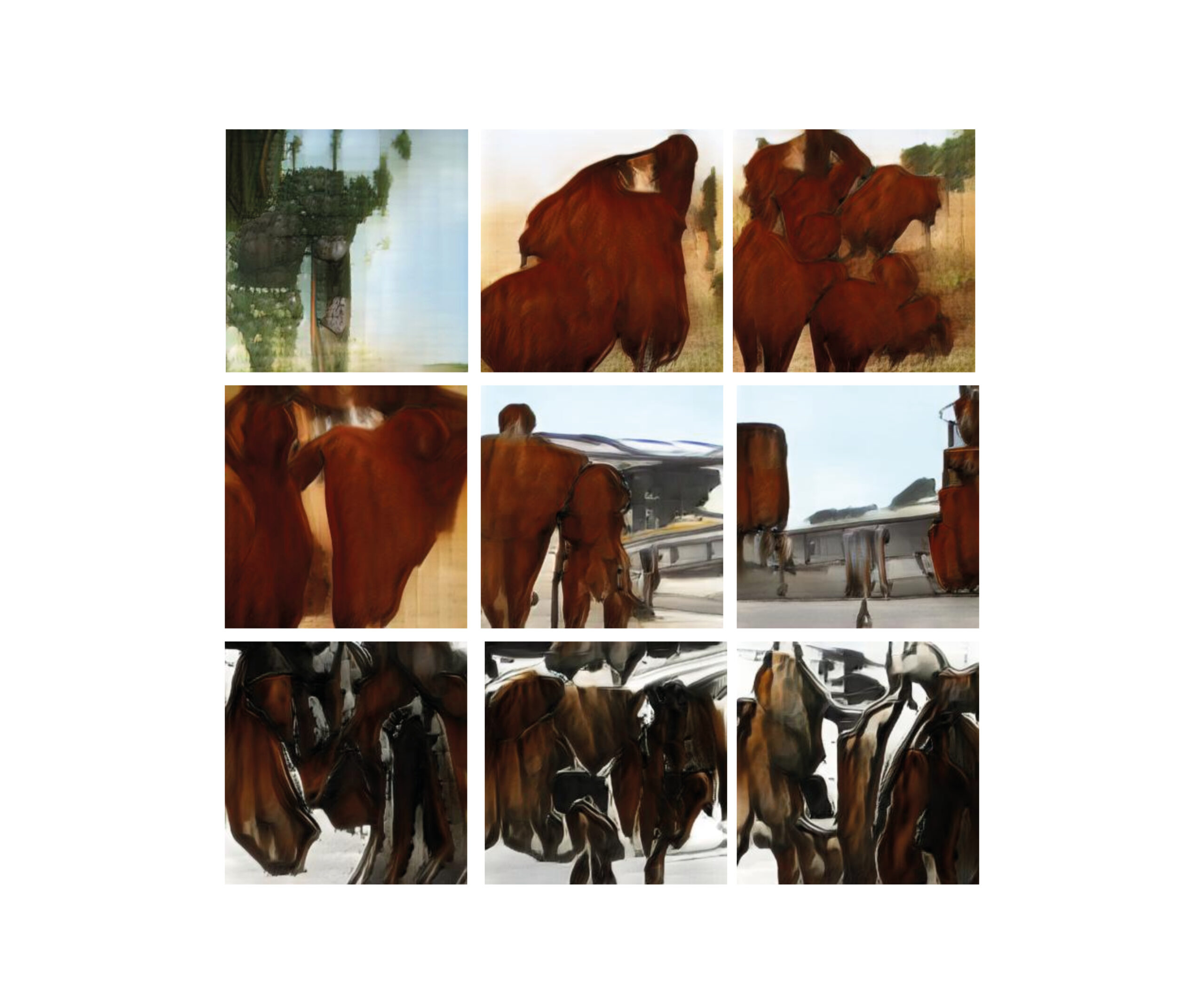

Images: Created by using RunwayML’s early StyleGAN tool (Style Generative Adversarial Network, or StyleGAN for short, is an extension to the GAN architecture introduced by Nvidia researchers in December 2018) the visuals depict the sentence: „Imagine two horses looking at an early automobile in the year 1900 and pondering their future.“ The AI-generated images emerged in shades of brown and gray, suggesting that the machine grasped not only the literal elements of the prompt but also attempted to contextualize them. The results hint at an early understanding of meaning within AI-generated imagery, subtly reinforcing the thematic depth of the installation.

To make a comparison I generated the same sentence in Midjourney in 2024, to demonstrate visually how quickly this technology progressed.

Audio: The voiceover was generated using Descript, which synthesized my own voice. To create this, the I recorded a 45-minute reading, allowing the platform to analyze and replicate my voice. The process raised deeply personal and ethical concerns—questions about control, misuse, and the implications of surrendering one’s voice to AI. The emotional weight of this decision became even more apparent when later on voice artists reacted to the project, expressing fears about the future of their profession. This highlighted for me one of the first creative industries at risk of automation, emphasizing the broader implications of AI in artistic and commercial labor.

Music: The soundtrack features a remix of Tigerlilly, a Drum and Bass track, reinterpreted by the AI composer tool Aiva. In 2020, Aiva required around 30 minutes to analyze and generate a new composition from the uploaded track. The resulting remix, while not groundbreaking, was surprisingly coherent, demonstrating AI’s ability to produce functional, if not deeply original, musical pieces. The process left participants astonished at how quickly AI could replicate and reinterpret human-created music.

Ultimately, every element of the installation—visuals, audio, and music—reinforced the central question: How will AI reshape the creative industries? At the time of this project, the term „generative AI“ was not yet widely used, but Two Horses anticipated its disruptive potential, making it an early exploration of AI’s role in artistic authorship.

Interpretative Commentary Two Horses is not an isolated experiment but part of an ongoing exploration into AI’s impact on creative industries and artistic authorship. My broader practice investigates the intersection of human and machine creativity, questioning how new technologies redefine artistic intent, labor, and perception. While this piece was an early foray into AI-assisted art, it laid the foundation for further works exploring generative AI, digital aesthetics, and the shifting dynamics of authorship in contemporary media.

Artist’s Statement or Quote

Art has always been shaped by the tools available to its creators, from the brush to the camera, from the synthesizer to the algorithm. Two Horses emerged from a simple yet profound question: Who is the artist when artificial intelligence is involved? Is it the human who provides the input, the machine that generates the output, or the audience that perceives and interprets the work?

This project was an experiment in surrendering control—allowing AI to generate visuals, music, and even my own voice. It was unsettling, exhilarating, and deeply personal. The act of training an AI with my voice raised fundamental ethical and emotional questions: What happens when my voice no longer belongs solely to me? Who controls what it says? These concerns are not just theoretical—they are real and immediate for many creatives today.

I see Two Horses as a conversation, not a statement. It invites the viewer to step into the role of the artist, questioning where authorship begins and ends. Inspired by Max Tegmark’s Life 3.0 and Gregory Clark’s Farewell to Alms, the piece draws a parallel between the obsolescence of horses in the industrial age and the potential displacement of human labor by AI. But unlike the horses of the past, we still have a choice: to define our role in this transformation, to rethink what creativity means, and to shape the future of art.

Ultimately, Two Horses is not just about AI—it is about us, our perceptions, and the stories we choose to tell.